The 2018 Grand Staircase Trip

The field trip expedition was funded by a grant from the National Geographic Society, and the technology development was funded by the University of Cambridge. Kathy Ho and Dave Berry from the LABScI team at Stanford started the trip in their home state of California, with Gemma Gordon and Anil Madhavapeddy from Cambridge joining them in Nevada. This expedition during the summer of 2018 spanned the states of California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona and Colorado, with the team visiting 15 National Parks, 16 National Monuments, a number of State Parks, Historic Sites, recognised Recreation Areas, and places of interest.

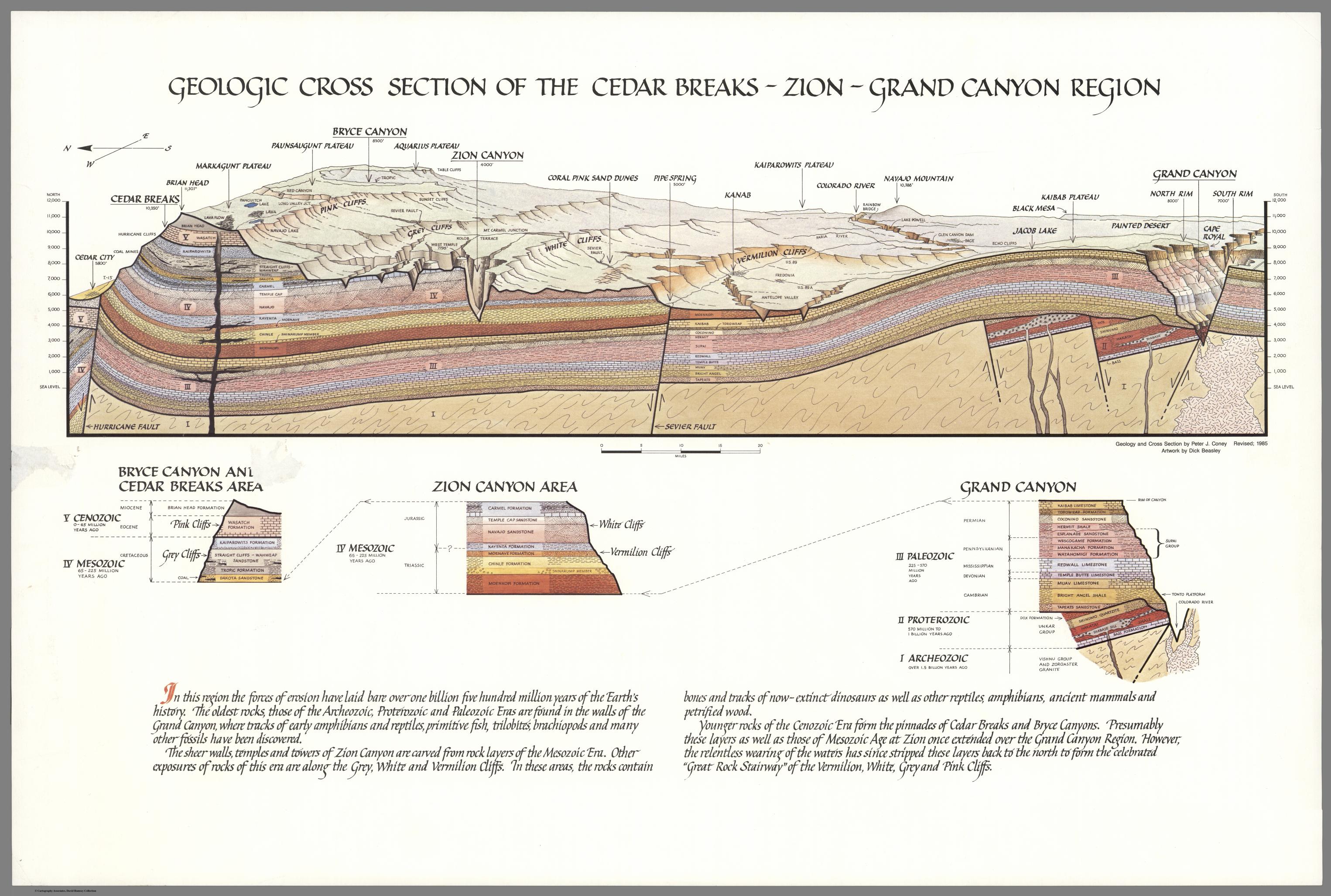

By Peter Coney, from the David Rumsey Historical Map Collection

By Peter Coney, from the David Rumsey Historical Map Collection

The Grand Staircase refers to a sequence of sedimentary rock layers found on the Colorado Plateau stretching from Cedar Breaks National Monument in the north, through Bryce Canyon National Park and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, down into Zion National Park and out to Grand Canyon National Park. In the 1870s, Geologist Clarence Dutton identified the concept of a staircase for the region, with each layer forming giant steps. He divided the formations into 5 steps going from youngest to oldest: Pink Cliffs, Grey Cliffs, White Cliffs, Vermillion Cliffs and Chocolate Cliffs. Modern geologists have since divided the steps into individual rock formations.

- Pink Cliffs

- Pink and red Claron Formation limestone found in Cedar Breaks National Monument and Bryce Canyon National Park

- Grey Cliffs

- Grey and white limestone and sandstone (lacking in iron oxide) in the Kaiparowits and Wahweap Formations round in Bryce Canyon National Park

- White Cliffs

- Navajo Sandstone found in Zion National Park, Capitol Reef National Park, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument and Canyonlands National Park

- Vermillion Cliffs

- Formations coloured by red iron oxide and bluish manganese found in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Capitol Reef National Park and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument

- Chocolate Cliffs

- Red sandstone in the Moenkopi Formation found in Grand Canyon National Park

The Grand Staircase is shaped by history, and a variety of processes spanning hundreds of thousands of years. These sediments were deposited at different points in history, ranging from 60 million years ago in Cedar Breaks National Monument to 1.8 billion years ago in the Grand Canyon National Park, and everything in between. 66 million years ago, these layers underwent uplift ranging from 5,000 (at the bottom of the staircase) to 10,000 feet (at the top of the staircase) after subduction movement of the Pacific Plate at the Hurricane Fault pushed up the North American Plate. Uplift increased the velocity and power of the Colorado River, which firstly eroded individual plateaus within the Colorado Plateau Province, and more recently (5-6 million years ago) began canyon-cutting, creating reefs and slot canyons.

- Arches National Park

- Arches National Park is located just north of Moab, Utah, and contains the highest density of natural arches in the world (over 2,000) amidst 119 square miles of desert. An evaporite salt bed lies beneath the park, which is responsible for the sandstone fins, arches and spires in the Entrada Formation.

- Bryce Canyon National Park

- Technically the main feature of this park is not a canyon, but a collection of huge amphitheatres that lie on the eastern side of the Paunsaugunt Plateau. These amphitheatres are home to thousands of hoodoos formed by freeze-thaw weathering and stream erosion of the rocks in the Claron Formation. Like Cedar Breaks, the higher elevation creates a cooler weather system with more precipitation than the lower, more arid areas along the Grand Staircase.

- Canyon de Chelly National Monument

- This landscape in northeastern Arizona preserves the ruins of indigenous tribes ranging from Ancestral Puebloans to the Navajo. It encompasses three major canyons: de Chelly, del Muerto and Monument, all carved by streams in the Chuska Mountains. Canyon de Chelly is owned by the Navajo Tribal Trust of the Navajo Nation, and is the only National Park Service location cooperatively managed in this way. The most distinctive feature is Spider Rock, a 750 foot high sandstone spire at the junction of Canyon de Chelly and Monument Canyon.

- Canyonlands National Park

- Located close to Arches, and the Utah town of Moab, Canyonlands National Park preserves a landscape of canyons, mesas and buttes eroded by the Colorado and Green Rivers. The area is split by the rivers into 3 desert districts with their own character: Island in the Sky (broad, level mesa overlook), the Needles (stripy rock pinnacles), and the Maze (remote and least accessible parts).

- Canyon of the Ancients National Monument

- Located just west of Pleasant View, Colorado, the site is managed by the Bureau of Land Management and contains the highest known density of archaeological sites (30,000) in the USA, with well-preserved evidence of native cultures. Examples include field houses, check dams, cliff dwellings, shrines, petroglyphs and agricultural fields.

- Capitol Reef National Park

- This remote park is located in south-central Utah and preserves 241,904 acres of desert landscape, colourful canyons, ridges, buttes and monoliths. It is known for the 100 mile long, 65 million year old Waterpocket Fold and the white capped Navajo Sandstone cliff domes that give the park its name.

- Cedar Breaks National Monument

- Located near Cedar City, Utah, Cedar Breaks is a natural amphitheatre of stripy Claron Formation sedimentary rock, 3 miles wide, and 2,000 feet deep. With elevation at over 10,000 feet above sea level, Cedar Breaks sits as the “Crown of the Grand Staircase” with a cooler alpine micro-climate and geological formations as “young” as 50 million years old. Due to its high elevation, parts of the monument are inaccessible during the winter months.

- César E. Chávez National Monument

- This monument commemorates Latino civil rights activist, César E. Chávez who was instrumental in establishing the country’s first permanent agricultural union. The site includes the headquarters of the United Farm Workers (UFW), César’s home, memorial garden and gravesite.

- Death Valley National Park

- This park straddles the California and Nevada border, east of the Sierra Nevada. It is the largest National Park in the lower 48 states, and is the hottest, driest and lowest (in terms of sea level) park in the USA. It is known for its harsh desert environment, valleys, canyons and mountains, with 91% of the park designated wilderness area.

- Devils Postpile National Monument

- An unusual formation of columnar basalt located near Mammoth Mountain in eastern California. The monument also protects Rainbow Falls waterfall on the middle fork of the San Joaquin River.

- Glen Canyon National Recreation Area

- This conservation area encompasses the area surrounding Lake Powell and lower Cataract Canyon, spanning the states of Utah (95%) and Arizona (5%). As the name suggests, the purpose of this land is for recreation as well as preservation (more so than in a National Park), and access to Lake Powell is provided via 5 marinas, 2 small airports, with 4 camping grounds and houseboats for summer rental. Lake Powell sits above Glen Canyon, which was flooded when the Glen Canyon Dam was completed in 1966. The GCNRA also includes the Rainbow Bridge National Monument (the world’s highest natural bridge) and Horseshoe Bend, an incised meander of the Colorado River.

- Goblin Valley State Park

- Located in the San Rafael Desert, Utah, this park is known for its thousands of hoodoos known as “goblins” that litter the valley floor. The goblins are created by differential weathering of the alternating layers of sandstone, siltstone and shale that form the Entrada Sandstone deposited 170 million years ago.

- Grand Canyon National Park

- The main feature of this park is the Grand Canyon, a gorge formed by the Colorado River after seismic activity uplifted the area known as the Colorado Plateau. The park is located in northwestern Arizona, and is the second most visited National Park in the USA.

- Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument

- This monument is the largest managed by the Bureau of Land Management, and protects some of the most remote land in the entire US - it was the last area to be mapped in the contiguous United States. It is comprised of 3 main regions: Grand Staircase, the Kaiparowits Plateau and the Canyons of the Escalante River. Presidential proclamation in 2017 has reduced the size of the monument from 1,880,461 acres to 1,003,863. The monument is known for popular hiking trails such as slot canyons Spooky and Peekaboo Gulch, as well as numerous dinosaur fossils estimated to be over 75 million years old.

- Hovenweep National Monument

- Hovenweep actually covers land in both Colorado and Utah, and is known for the six groups of Ancestral Puebloan villages that were occupied until the 14th century. There is also evidence of occupation by hunter-gatherers from 6,000 BC-200 AD. The monument has also been designation as an International Dark Sky Park.

- Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site

- This trading post in Arizona was built by John Lorenzo Hubbell to facilitate trade between the native Navajo people and settlers in the area. The Navajo people were forcibly relocated to New Mexico by the US government between 1864-1866 in what was called “The Long Walk of the Navajo”. The trading post represents a landmark in history after this period, where Navajo people on the newly-created reservation could sell their handmade products to ease the economic depression following the Long Walk.

- Joshua Tree National Park

- Named for the Joshua Trees native to the Mojave Desert, this National Park lies just east of Los Angeles, near Palm Springs, California. It includes parts of the elevated Mojave Desert, and the lower Colorado Desert, with ecosystems distinct to each. The Mojave Desert section features lots of loose boulders suitable for climbing and scrambling, and sparse flatland with the distinctive Joshua Trees. The Colorado Desert section showcases mixed bush scrub, areas of dense cactus and desert dunes.

- Kings Canyon National Park

- Jointly administered with Sequoia National Park, this park is named for Kings Canyon, the glacier-carved valley over 1,600 meters deep. The majority of the park is designated wilderness, and Grant Grove is home to the second largest tree in the world, giant sequoia General Grant.

- Manzanar National Historic Site

- One of 10 American internment camps where 110,000 Japanese Americans were held during World War II from 1942-1945. It is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada in California. Manzanar translates as “apple orchard” in Spanish, and before the war was an area inhabited first by Native Americans, and later by European Americans.

- Mesa Verde National Park

- The park in Colorado protects some of the best-preserved Ancestral Puebloan archaeological sites in the USA, including the well known Cliff Palace structures.

- Mojave National Preserve

- Located in the Mojave Desert in California this preserve protects 1,600,000 acres of land including the Kelso Dunes, Marl Mountains, Cima Dome and volcanic features such as Hole-in-the-Wall and the Cinder Cone Lava Beds.

- Montezuma Castle National Monument

- Located in Camp Verde Arizona, this is neither a castle (in the traditional sense) nor related to the Aztec emperor Montezuma. It is a set of well-preserved dwellings built and used by the Sinagua people between 1100-1425 AD.

- Natural Bridges National Monument

- Located just northwest of the Four Corners boundary in Utah, this monument contains three natural bridges: Kachina, Owachomo and Sipapu, the thirteenth largest natural bridge in the world. Natural bridges are eroded by flowing streams or rivers in the base of a canyon, and will enlarge over time until they eventually collapse under their own weight.

- Navajo National Monument

- The monument is located in the northwest portion of the Navajo Nation in northern Arizona, and preserves 3 cliff dwellings of the Ancestral Puebloan People: Broken Pottery, Ledge House and Inscription House.

- Peekaboo Gulch

- This is a short but physically demanding hike that requires some rock-climbing and scrambling to navigate the tight, twisty slot canyon. This fun, multi-level adventure is often combined with Spooky Gulch to make a 3.5 mile long hike.

- Petrified Forest National Park

- This National Park straddles Navajo and Apache counties in northeastern Arizona, and is named for large accumulation of petrified wood. The south of the park is strewn with fallen trees from 225 million years ago deposited by streams flowing across the floodplain, buried quickly by sediment of the Chinle Formation, and later fossilised. The north of the park showcases eroded badlands: steep slopes deposited layers of sediment that have been extensively eroded by wind and water.

- Pipe Spring National Monument

- The water of Pipe Spring was crucial to the survival of the Ancestral Puebloans and Paiute Indians for 1,000 years. The Mormon missionary expedition of 1860s also settled here and started a large cattle ranching operation. The site details the human history of the area over time, acting primarily as a memorial to western pioneer life.

- Rainbow Bridge National Monument

- Located within the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Rainbow Bridge is the world’s highest natural bridge, with a height of 290 feet. Historically, access to the bridge was difficult and time consuming (a difficult 3 day hike) but the popularity of activities in Glen Canyon has reduced it to a 2 hour boat ride on Lake Powell followed by a mile long walk.

- Rattlesnake Canyon

- Rattlesnake Canyon is another slot canyon, located nearby the more famous Antelope Canyon, in Arizona. It is more similar in shape to Lower Antelope Canyon than Upper Antelope Canyon, with a more dynamic twisted shape and steep areas with ladders to climb.

- Sequoia National Park

- Located in the southern Sierra Nevada, California, this park protects 404,064 acres of forested mountain terrain. Sequoia is south of, and contiguous with Kings Canyon National Park. Known for its old-growth giant sequoia forests, the park encompasses the Front Country (accessible woodlands and grasslands) and the Back Country (a roadless, wilderness accessible only by foot or horse).

- Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument

- Sunset Crater Volcano is a cinder cone located just north of Flagstaff, Arizona. It erupted in 1085 AD, spewing lava and ash that caused the local Sinagua to abandon their settlements. The volcano is the youngest of the San Francisco Volcanic Field, and while it is considered extinct, other volcanoes in the string are active, with eruption in the future very likely.

- Spooky Gulch

- This short slot canyon hike is located within Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, and is named for its deep, dark and extremely narrow walls. It is often combined with Peekaboo Gulch to form a fun and interesting loop.

- Tuzigoot National Monument

- This monument preserves a 3-story pueblo ruin containing 110 rooms, built above the Verde River floodplain in Arizona. Tuzigoot is Apache for “crooked water” and possibly refers to Pecks Lake nearby.

- Upper Antelope Canyon

- Antelope Canyon is a famous slot canyon in Arizona, within protected Navajo land. It is split into two separate canyons, referred to as Upper Antelope Canyon or “The Crack” and Lower Antelope Canyon or “The Corkscrew”. Tours are only accessible by guided tour. Flash flooding has shaped the canyon, eroding the walls of Navajo Sandstone creating deep corridors with smooth flowing edges. Flash flooding is still common, especially during monsoon season.

- Valley of Fire State Park

- This nature preservation area is located just south of Overton, Nevada, and is named for the red Aztec Sandstone formed from sand dunes 150 million years ago. Under full sun, these rock formations appear to be on fire. This park is Nevada’s oldest state park, and lies within the Mojave Desert.

- Walnut Canyon National Monument

- This 600 feet deep canyon just southeast of Flagstaff, Arizona is known for the cliff dwellings built by the Sinagua people. Several species of walnut trees call the canyon home, and maintained trails provide access for tourists to view the dwellings up close.

- Wupatki National Monument

- Located near Flagstaff, Arizona, this monument is rich in Native American ruins, with settlements built by the Ancient Pueblo People (Cohonina, Kayenta Anasazi and Sinagua). Wupatki means “Tall House” in Hopi, and may refer to the largest structure on the site, a multi-story Sinagua pueblo dwelling comprising over 100 rooms.

- Yosemite National Park

- Located in the western Sierra Nevada of Central California Yosemite is known for its waterfalls, granite cliffs, deep valleys, ancient giant sequoia groves and meadows. Almost 95% of the park is designated wilderness.

- Zion National Park

- Featuring the prominent Zion Canyon (15 miles long and 2,640 feet deep), Zion National Park boasts unique geography and an unusual diversity of flora and fauna. Located in southwestern Utah, the Park includes mountains, canyons, buttes, mesas, rivers, slot canyons and natural arches. There are a number of well-known trails in the park such as Angels Landing (a lofty and narrow protrusion of broken sandstone), the Narrows (a narrow gorge on a fork of the Virgin River) and Weeping Rock (a water spring “weeping” through the porous Navajo Sandstone).

Arches National Park

After a brief visit to Goblin Valley State Park (which has some pretty fun and interesting hoodoo formations), we're spending a few days in Moab so that we can visit Arches and Canyonlands. Because we had an early afternoon meeting with the ranger in charge of education for both parks, we didn't have time for a long hike. Instead, we stopped at several roadside attractions.

Our first stop was to Balanced Rock, a 128 foot tall sandstone formation that shows how the forces of erosion can shape the various rock layers at different rates. The top rock, Entrada Sandstone, sits on a mudstone pedestal known as Dewey Bridge Member of the Carmel Formation, which erodes much faster. Some day, the Dewey Bridge portion will weaken to the point that Balanced Rock will collapse.

Our next stop was the Windows Section, where several arches can be seen close to the road. My favorite was Double Arch, which started as a pothole and grew in size until water breached the sandstone and created a hole in the ceiling. At the same time, the 'walls' of the rock were also eroding, creating the double arches.

After meeting with Rangers Heidi and Michael, we decided to check into our hotel and grab dinner. The hotel, Adventure Inn, is 100% solar! Makes us feel good that we're spending 3 nights here.

In the early evening, we decided to hike up to Delicate Arch before going to the evening ranger talk. It was still hot and crowded, but the view from the top was fantastic. We also went to the lower viewpoints, and it was amazing to see how far away (and how isolated) Delicate Arch is.

The ranger program for the night was actually quite different from the ones we've had in the past - about cars in the parks and the changes (and, sometimes, the destruction) caused by putting in motorways. The ranger seemed to pose the problem, but let us talk about it and didn't give us a solution. On the one hand, having roads and accessibility allows more people to enjoy the park, but it does bring in more pollution, crowding, and puts roads through the wilderness.

That night was the first clear night we'd had, so we were excited to get the chance to stargaze. The only downside was that the moon, which is less than a week from being full, was setting at 2:30 AM - meaning it was fairly bright out even though we were deep inside the park. We stopped first at Panorama Point, which gave us a fairly unobstructed view of the night sky, and we tried our best to block the moon and take pictures. Without any background formations, it was hard to make anything look good, so we moved to Balanced Rock for another try. The moon was still fairly bright so we took a nap, then tried again at around 2:45. Our skills and equipment weren't great, but it was still fun getting to see the Milky Way.

Two days later we returned to the park, mainly because we got guided ranger tour tickets, but it was nice to have more time to hike. We got an early start and headed out into Devil's Garden, taking the Primitive Trail. There are many famed arches along this route, and because it is a bit more difficult with some steep slopes and some rock scrambling, there were much fewer people to share the trails with the further along we got.

The first major arch we got to was Landscape Arch, a 306 foot long, really thin arch that looks like it is about to collapse. In fact, a 60-foot long slab fell from it in 1991... and every year, as more precipitation seeps into the sandstone and the freeze-thaw cycle weakens the rock, the closer it is to its end.

We continued along the trail, stopping at the various arches, then took the Primitive Trail back around to the start. It was fun scrambling around on the fins and canyons, and seeing the different stages of arch formation (and collapse).

After going back to the hotel for a bit of a rest, we went back into the park for our Fiery Furnace hike. This area requires either a permit or a ranger-led tour, so we were lucky to get spots on one of the 14-person hikes. And it was definitely worth it - the area is well protected and much quieter than other parts of the busy park, and there are many canyons, arches, and fins in a small area. There were lots of dead-ends and no trails or markers, so I'm glad we had a ranger guiding us. And despite the name, Fiery Furnace is more sheltered from the sun and has a nice breeze blowing through the canyons, so it was much cooler inside.

Bryce Canyon National Park

This morning we were lucky to meet up with a friend of a friend Adam, a professional hiking guide, and his wife Shauna, a ranger at Zion, who came into Bryce and joined us to hike the Navajo/Peekaboo loops. Adam leads hikes around the southern Utah area, but since it is the low season (too hot for most people, apparently!), he was excited to get out and hike.

We started down into the hoodoos via Wall Street, a steep switch-back trail into a canyon with high, straight walls that leads to some incredible views. Bryce Canyon is actually inaccurately named - it isn't a canyon (which is formed by a river between two walls), but instead a series of amphitheaters. The top of Bryce is a plateau, formed by soft limestone of the Pink Member of the Claron Formation. As slightly acidic rainfall dissolves the limestone, it leaves lumpy, bumpy sides. Fins form out of the cliffs, which may eventually form windows due to the freeze-thaw process, and when the windows collapse, individual hoodoos are formed.

The tops of the Bryce Canyon hoodoos are capped with dolomite, which are more durable and helps protect the weaker limestone underneath. But eventually, the hoodoos will also collapse, forming the rounded hills known as badlands. At Bryce, hoodoos erode at the rate of about 2-4 feet every 100 years, so in about 3 million years it will reach the Sevier River.

Getting to hike down among the hoodoos was a great experience, allowing us to see up close what the hoodoos looked like. Every turn brought us a new vista, and halfway down the Navajo Loop Trail we cut over to do the Peekaboo Loop. Towards the end, it started to rain but we just happened to be by a large alcove with benches, so we waited out the downpour. In the meantime, we even saw a rattlesnake.

After the rains, the weather was much cooler and the rest of the hike was pleasant - even the steep uphill back to Sunset Point, where we had a nice view of Thor's Hammer. We had a picnic pizza lunch with Adam and his family, then went to the visitor center. The ranger suggested we drive out to Rainbow Point at the far southern end of the park, so we did the Bristlecone Loop trail to see the views at the end of the park and to see the Bristlecone pine trees.

The next morning, we did the Fairyland Loop trail, an 8-mile hike that goes down into the Bryce Amphitheater on the North side, as well as going along the plateau rim. Since it is one of the longer, harder day hikes, there weren't many people on the trail. For much of it, we had the peace and quiet to enjoy the hoodoos on our own. After stopping for a snack at the Tower Bridge, we hiked back up to the Rim and started back to Fairyland Point when the long, loud rumblings of thunder started, We were about half a mile from the car when it started hailing, so our last bit of hike was actually a run... a fun way for Gem and Anil to end their Parks trip.

Canyon de Chelly National Monument

Canyon de Chelly is remarkable in that is is one of the few NPS sites that has a large community of people living in it. The Navajo people still farm and ranch on the canyon floor, and aside from one trail, access into the canyon is by permission only.

The park actually consists of two different canyons, that join together at the entrance of the park. Two rim drives give excellent overlooks; the South Rim looks over Canyon de Chelly, and the North Rim looks over Canyon del Muerto.

We started at the Visitor's Center, where we talked to one of the Park Service police officers, Ranger William. He gave us his thoughts about the park, but really wanted us to talk to his brother, an interpretive ranger. So we set off to explore the park before coming back to meet

him.

We drove through the South Rim, stopping first at Tunnel View for our first glimpse into the canyon. It was surprising to see how green and lush the floor is; there are thriving farms there, because of a slowly meandering river as well as a layer of limestone (broken off from the surrounding cliffs) that trap moisture near the surface.

On our next stop, Tsegi Overlook, we decided on a picnic lunch. While there, we met a native Canyon de Chelly resident, Corey, who was just sitting under a tree, "waiting for a ride." We offered him some food and water, and eventually gave him a ride to his house. We drove to the end of the South Rim Drive, Spider Rock Overlook. According to Navajo legend, this is where Spider Woman lives and came down to teach humans how to weave. We also stopped at Face Rock Overlook and Junction Overlook before returning to the Visitor's Center to meet with Ranger Justin.

Justin is also a Navajo who has lived in Canyon de Chelly his whole life. The Navajos actually asked the US Government to step in and help protect the area, which is how the Monument was created. The canyon floor is almost all closed to visitors unless you have special permission or go with a licensed guide. The only exception is the White House Ruin Trail, which goes down to an ancient Pueblo ruin on the valley floor.

That night, we stayed in Chinle - forgetting it was July 4. It’s a small town, and every restaurant we went to was closed... our choices ended up being Denny's or Churches Chicken. Chicken won.

The next morning, we left the park via the North Rim Drive, which follows Canyon del Muerto. There are only 3 overlooks - Antelope House, Mummy Cave, and Massacre Cave, but they are just as spectacular as the Southern overlooks and you get a closer look at the Pueblo ruins.

We left Canyon de Chelly via Ship Rock, a monadnock that rises up in the desert of New Mexico like the prow of a ship, before heading out to Cortez, Colorado.

Canyonlands National Park - Islands in the Sky District

We got a rather late start the next morning (since we didn't get to bed until around 4AM), so we had a bit of a leisurely day at Canyonlands. After stopping at the Visitor's Center for Gem and Anil's Junior Ranger Badges, we set off into the park.

Formed at the confluence between the Colorado and Green Rivers, Canyonlands is divided into three main districts. To the west, the Maze is more rugged and difficult to get to - it's a backcountry area with no paved roads. To the east is the Needles District, which we visited about 2 weeks ago, is named for the many finger-like spires throughout the landscape. And at the top of the 'Y' is Islands in the Sky, the mesa that looks out over the entire landscape.

The scenery here is spectacular, with huge mesas, canyons, and buttes that are unlike anything I've ever seen. We stopped first at Mesa Arch, with gave us our first view of the surrounding valley. The arch itself was right on the edge of the cliff, with a great window to the landscape.

And the landscape is so interesting! It's like a reverse-topographical map, with so many layers, leading down into canyons formed by the two rivers and their tributaries. But it’s much shallower but vaster than the Grand Canyon. It is really fascinating to see how differently this area looks, since it too was created by river erosion (the Green and Colorado Rivers also shaped this area).

From Mesa Arch we drove down to the Grand View Point, stopping at various overlooks to see the canyon. The Grand View Point tapers to the junction of the 'Y', looking both at the Colorado River and the Green River. If not for a huge mesa right at the tip of the overlooks (one of the "Islands" of the Islands in the Sky), you'd be able to see the actual Confluence, where the rivers meet.

On a side note: do you know the difference between a mesa and a butte? A mesa (Spanish for 'table') looks more like a table - wider than it is tall. A butte is taller than it is wide - like a bar stool.

On our last day in Moab, we had a final morning in Canyonlands. We were all still really curious about the landscape, so we made it a point to make it to one of the ranger talks on geology. Before that, we decided to visit Aztec Butte, a short hike to see some Ancient Puebloan granaries and views from the top of the butte. It was a surprisingly steep hike up the slickrock, but it had some great views across the canyon.

The final hike was to Upheaval Dome, a curious crater with a large dome in the middle, that has puzzled geologists. Some believe it was created by a salt dome collapsing underneath, but we preferred the theory that a giant meteorite vaporized on impact, creating the crater. Whatever its origins, it has curious patterns of rings when viewed from above, and from the overlooks, you can see the domes and spires that protrude from the inner dome.

Canyonlands National Park - Needles District

Canyonlands is an interesting park, because it is divided into three main districts. Since we were already in the general area, we decided to visit the Needles District - not as popular as the Islands in the Sky, but interesting nonetheless. On our way in, we stopped at Newspaper Rock, an interesting panel with petroglyphs dating back over 2000 years. They don't really know what the figures mean - maybe messages, maybe prayers, or maybe just ancient graffiti. Even so, it was pretty impressive to see.

In Canyonlands, we stopped to see the main overlook into the Needles. This area was created when sandstone began shifting over a layer of salt leftover from an ancient sea. This caused the sandstone to fracture in parallel cracks, which gradually eroded the exposed rock. Over time, it eroded into spires known as the Needles.

It was also interesting to see the potholes in the sandstone. We hiked around Pothole Point, which was dry now that it’s summer, but for a few months, fill with rainwater. During this time, lots of different organisms thrive in the tiny pools, some living their entire life-cycles in a few short weeks. They lay eggs, which lie dormant during the dry season, until it because wet enough for them to hatch. Animals such as tadpole shrimp, fairy shrimp, toads, and winged insects all live in the potholes.

Canyons of the Ancients National Monument

We headed out of Colorado via Canyons of the Ancients - an unexpected detour that brought us to two pueblo ruin sites. The first was Lowry Kiva, a 40-ish room pueblo built in 1060AD. The best part was being able to go down into the large kiva, being able to see it from ground level rather than from above like every other kiva. The other structure on the site was the Great Kiva, a strange building with two huge stone figures built into the ground. Supposedly they represent summer and winter, though I thought they looked more like animals.

The next stop, which we did as a bit of an afterthought, was to Painted Hand Pueblo. This was an unexpected find down a bumpy dirt road, with a 13th century tower perched on a rock overlooking the canyon. Underneath was a small alcove, with several pictograph handprints painted on the back of the rock wall.

Capitol Reef National Park

The story of the Colorado Plateau has been heard in the parks all throughout the area, but Capitol Reef is one of the more geologically interesting parks. During the tectonic events of the late Triassic, the Pacific Plate slid beneath the North American Plate, causing the layers of Earth's crust above the faultline to bend and fold. The western side grew over 7,000 feet higher than the eastern, in an uplift known as a monocline, with older rocks on the west and newer rocks on the east. This 100-mile long warp is known as the Waterpocket Fold.

Throughout the park, there are 19 different geologic layers that can be seen, representing 280 million years. Erosion in the last 20 million years (with most of the canyon-cutting within the last 6 million years) has given the park the many unique shapes - from arches and spires to twisting canyons, monoliths, and domes.

We spent the day doing the Loop the Fold drive, going down the Notam-Bullfrog Road (parallel to the Waterpocket Fold along the Eastern side) and cutting across the Burr Switchback Trail and back around to Fruita. Along this route, there are many different landscapes, including a checkerboard sandstone mesa dotted with lava boulders, a field of fossilized oyster shells from a 95-million year old marine delta, and the steep tilt of the Waterpocket Fold.

We returned to Capitol Reef for the day, to meet with Ranger Lori and to see the Scenic Drive. We started by going to the Gifford House to see if they had any fruit (no, since they sold out pretty much after 5 minutes of opening), though we did pick up two more pies. We met with Lori, who had the best reaction to the VR machine - and who was really supportive in our project and what we were doing.

She also facilitated our meeting with Amanda, the head of the orchards, so that we could get footage of the trees and fruit-picking. Amanda and Montana took us into the Jackson Orchard, where we were able to get some footage (and a bit of a taste!) of fresh apples picked from a tree. Lori's idea was that most kids don't know where their food comes from, so seeing the experience of picking an apple would most likely be new to many people.

Before meeting Amanda, we went up to Petroglyph Panel to see the 800-1000 year-old petroglyphs. They were further away and harder to see than some (eg Newspaper Rock), but the design was different (having been done by the Fremont Culture, contemporaries to the Ancient Puebloans who were South of the Colorado River).

We then hiked the Hickman Bridge Trail, with views of the Capitol Dome (which Capitol Reef is partially named). Probably the most popular thing to do at Capitol Reef is to see the Scenic Drive, which goes past Fruita through some really amazing landscapes.

We took the dirt road out to the end of Capitol Gorge, then hiked a bit our onto the wash until we saw the old Pioneer Register - a huge rock wall with old graffiti, where pioneers from the late 1800s - early 1900s carved their names.

Because there was thunder and dark skies, we worried a bit about getting trapped out on the wash and turned back early. We did get a chance to go down Grand Wash and see some of the old uranium mines, before heading back to Fruita where we had more pie. Delicious.

Cedar Breaks National Monument

After a stopover in Vegas to pick up Anil and Gemma, we headed to Cedar Breaks - one of the lesser-known parks in Utah. Unbeknownst to us, the park is famous for its wildflowers, and we arrived in time for the best viewing.We went on a ranger talk, learning about several of the endemic wildflowers that were currently blooming. Cedar Breaks is actually known for the 'amphitheater', a canyon eroded by freezing and thawing water that breaks down the layers of limestone that had been formed by the shallow seas that once covered the area. With no river or stream system, the erosion creates different formations - hoodoos (fingerlike towers), rather than arches or bridges. Cedar Breaks is commonly compared to Bryce Canyon, but at 10,350 feet in elevation, it's much cooler (temperature-wise!) and has a very different look.

The only problem was that we had timed our trip for the new moon and the Star Party (since Cedar Breaks is an International Dark Sky Park), but it was overcast and stormy almost the entire time we were there. We did have a great geology talk from Ranger Zach, who also talked to us for a while about his thoughts on the park and what we should be sharing to our students. In between, we went up to Brian Head Peak (the highest part of the park), and also went down to Brian Head for dinner. We actually went to the peak twice - the first time, it started raining pretty hard and Anil didn't even make it past the car; the second time, we had a slow drive up so that we could watch the marmots playing around on the rocks.

We stopped at Sunset Overlook for a view of the entire amphitheater (but the sunset was basically hidden by the clouds - bummer), and the stargazing was canceled but we did go to Zach's astronomy talk. It was quite good, talking about the importance of dark skies and giving fairly easy ways that individual people can help - namely, by making sure lights are pointed in the right direction (not up towards the sky), are turned off if not needed, and are a warmer color.

Cedar Breaks as a storm rolls in

Cedar Breaks as a storm rolls in

Cedar Breaks was established as a National Monument in 1933, and is formed of a natural amphitheatre with multicoloured cliffs consisting of shale, limestone and sandstone. As with its sister park Bryce Canyon National Park, arches, windows and hoodoos are in abundance. Interestingly, there are no cedar trees here at all - it’s likely that settlers mistook the many juniper trees for cedar, and the name stuck.

- Geology

- Cedar Breaks is located at the top of the Grand Staircase, standing at over 10,000 feet above sea level. Compared to the Grand Canyon (1.8 billion years old) which forms the bottom of the staircase, it’s rather young at only 50-60 million years old. As with the whole area of the Colorado Plateau, the amphitheatre here was formed from a combination of processes: deposition, uplift and subsequent erosion.

- Deposition

- 60 million years ago, Cedar Breaks was a flat area of land that lay between a shallow sea to the east, and huge mountain ranges to the west. Shale, limestone and sandstone were deposited at the bottom of an ancient lake here (Lake Claron), together with trace amounts of iron. Deposition continued for ~25 million years, creating the vibrant layers of the Claron Formation (deep red, warm orange and dusky pink) capped with white tuff formed from settled volcanic ash ejected and blown 100 miles east from Nevada ~30 million years ago.

- Uplift

- Nearby tectonic activity continued, and ~20 million years ago subduction at the Hurricane Fault caused the Colorado Plateau to uplift and tilt, elevating Cedar Breaks by 8,000 feet. This uplift uncovered the compacted layers of sedimentary rock, fracturing them in places and exposing them to the elements.

- Erosion

- The Colorado River (along with other rivers) is responsible for creating canyons throughout the length of the Grand Staircase, but there are other forms of erosion that take place at the upper elevations. As with Bryce Canyon (not actually a “real” canyon), the different geologic formations visible at Cedar Breaks are formed by a combination of falling rain, freezing ice and gravity. Falling acid rain seeps into fissures in the rock formations and reacts with the calcium carbonate present in the layered Claron formation, and slowly dissolves the limestone, enlarging the gaps further. The temperature commonly drops below freezing, and this water turns to ice expanding the fracture further, then melts and erodes the rock as it follows gravity down. This repeated action of freeze-thaw forces the rocks to break and fracture further, creating fins, arches, hoodoos and windows.

Death Valley National Park

From Manzanar, we drove to Death Valley via Lone Pine. On the road in, we stopped at Father Crowley Vista, overlooking the western valley. As we were driving in, we could just see the mouth of what looked like a big hole - you couldn't really see what the shape was or the depth, but you couldn't see the bottom. From the vista, it became clear that it was the mouth of a huge gulley that wound down the side of the mountain, opening onto the valley floor. We stopped for a few pictures at the overlook and at the end, driving down a bumpy dirt road. Along the way there were three men sitting on camping chairs, looking like they were settled in for a day of fishing. On our way back we decided to stop and ask what they were looking for - and it turns out, they were airplane spotters - regulars who come all the time to take pictures of the jets. Some of the pilots even know them and will put messages into the cockpit that can be seen in zoomed-in photos.

I'd heard of this place (but forgotten it) - known as Star Wars Canyon, the military uses the area for low altitude maneuver training. It is always a hit or miss whether you'll see a fighter jet - some days, there are none, but that day they had already seen 16 (the man I was talking to had been there since 5AM!!) We all doubted we'd see one, but it was so interesting talking to them - the fighter pilots call the maneuver into the canyon and out into the valley the "Jedi Transition" and from the vantage point that we were standing, you could see almost the entire length of the route. We chatted for about 40 minutes and were just getting ready to leave, when suddenly Dave saw a speck in the horizon approaching - it was an F-18 Hornet fighter jet, coming in for a pass.It zoomed into the canyon at around 500 mph, banking and swerving through the turns. It then went into the valley and swooped around for another pass, this time much slower (so I pulled out my cell phone and actually got some pictures!!). It then came around a third time, again even slower and higher, to the point where some of the pictures showed two helmeted figures in the cockpit. We're sure they could see us all jumping and waving, and I’d like to think they slowed down just so we could have some good pictures. Bo (James Reeder), one of the "regulars"; sent us his pictures of the plane since he had huge cameras with telephoto zoom lenses.

The next morning, we had a 9AM meeting with Ranger Brandi in the Furnace Creek Visitors Center. We left at 7:30 and by the time we got to the VC it was already 104 degrees. Brandi had good info - about the formation of the valley and why it stays so hot, as well as ideas on things to focus on (Badwater Basin and the salt flats was her "can't miss" location, since it is unlike anywhere else in the world. We earned our junior ranger badges, then set out to explore the park.

First up was Badwater Basin, the lowest point in North America at 282 feet below sea level. We walked out into the salt flats and took a detour to get away from the crowds - found an area with new salt and lots of wet ground. Can easily see how the area is close to the level of the aquifer. The water was originally from Ice Age snow and rain that travelled hundreds of miles from central Nevada. The bedrock is a porous limestone, and the aquifer ends along a fault line at the base of the mountain at Badwater. Salts from old deposits combine and flow down, ending at the lowest elevation. When the water evaporates, it leaves the concentrated minerals. It's named Badwater that because a prospector couldn't get his mule to drink from the water, so he wrote on his map that the spring had "bad water".

Devil's Golf Course was formed by crystallized salts, shaped by winds and rain. This area, along with Badwater, really show how many minerals are present in the area.

Artist's Drive/Artist's Palette is maybe my favorite place in Death Valley. It truly is a palette of colors - pinks, oranges, yellows, and blues all on the same area of rock. The colors are formed by different minerals caused by variations in oxygen levels and elements present when volcanic eruptions 5 million years ago first deposited the ash and minerals that make up the mountain. The minerals include iron, aluminum, magnesium, and titanium, as well as red hematite and green chlorite. Surprisingly, there is no copper here even though there is a greenish blue that looks just like that of a copper dome.

The Keane Wonder Mine was one of very few profitable gold mines in Death Valley, running from 1904 to 1917 and producing over a million dollars in gold. They even used some of the gold mined here to make coins to pay their employees.

The Ubehebe Crater is actually an explosion crater, formed when a superheated combo of steam and rock explodes to create a crater. It’s actually fairly new, at around 2,000 years old. Makes you wonder what kind of volcanic activity is going on under us right now, and whether anything else is getting ready to explode.

Since we were in the valley already anyway, we had dinner at the diner in Furnace Creek and went on an evening hike up Golden Canyon. This is one of the most popular hikes in Death Valley; back in the day, it used to be paved and people could drive up to see the canyon; now, only some of the pavement remains. We started a little after 7pm, but is was still over 100 degrees out. We hiked about half a mile in, having much of the hike to ourselves which made for some good 360 photos. On our way back, we saw both bats and a kit fox on the side of the road.

We got up early (5:45AM!) the next morning in order to pack up the car and be out as early as we could, to take advantage of the cooler weather. Our first stop was Mesquite Sand Dunes - our goal was to look for evidence of animal activity from the night before. It was before 7AM and there were a handful of cars already in the parking lot, so we wondered if we'd have to wander far to see undisturbed tracks. But not too far in, we found our number one wish - sidewinder tracks! We tracked it back a ways, where we could see where it slid headfirst down a slope and continued its way across the sand.

We also found what we think are tracks from a kangaroo rat, roadrunner, stink bug (or some other beetle), and kit fox (or other small canine). We also found the burrows of what we think are a kangaroo rat and a sidewinder (based on the number of tracks right outside.

After the sand dunes, we backtracked a bit to go into Mosaic Canyon, an area where a mix of several different rock types form colorful walls, shaped by major flash floods every few decades. We didn’t hike too far in (as it was nearing 100 degrees and we weren't wearing hiking shoes), but did go through all the fun parts at the beginning of the canyon.

We then stopped at Salt Creek (where, in the spring, you can find pupfish) - but it's now dried up. Dozens of zebra lizards, very white to camouflage themselves on the dried creekbed, dart around or stand with their bodies far off the ground to stay of the hot hot sand. There were also giant Western horse flies - about 3/4 of an inch long, that bugged us (haha, see what I did there?) the whole time - one even bit Carrie through her shirt.

Near Furnace Creek is the Harmony Borax Works, built in 1882 for the borax found on the salt flats. They had to refine the borax first because of the prohibitive cost of transport, which consisted of 20-mule teams carting the borax 165 miles across the desert to the nearest train station.

Our next stop was Zabriskie Point, where we could see the colorful badlands down into the valley. The clay, sandstone, and siltstone buildup from a long-ago lake used to be flat, but seismic activity and pressure folded up the valley floor, and periodic rainstorms caused gullies in the eroded soft rocks.

20 miles up from Zabriskie is Dante's View, overlooking Badwater Basin and the rest of the valley. It was named purely as a PR move for tourism, but it is definitely a great panoramic overview of the entire Panamint Range.

We're now in Henderson/Las Vegas, and will be dropping off Carrie tomorrow before heading out into Arizona.

Devil's Postpile National Monument

On the Eastern side of the Sierra Nevadas is Devil's Postpile, a columnar basalt formation created almost 100,000 years ago. Glacial moraines had formed a dam that stopped a flow of hot lava, creating a 400-foot deep pool. When it cooled, cracks formed at the top and bottom of the pool to release built-up tension. The cracks turned into hexagons (because nature loves 120 degree angles), and traveled through the cooling lava until the columns were formed. But they were still hidden until the last ice age 20,000 years ago cam along and a glacier exposed the cliff. Along the top of the Postpile, you can see the striation marks caused by the carving glaciers.

Getting to the monument took a few tries - you have to take a shuttle from the Mammoth Ski Resort, and after getting some wrong information about where the visitor center was (there isn’t one), we barely made it onto the next bus up to the monument. We made it to the Ranger Station with about 20 minutes to spare, and got some great information from Ranger Monica. She was even nice enough to give us our Junior Ranger patches, even though we weren't finished with our booklets, and the other ranger let us buy a pin and patch even though the store was technically closed.

On our way back on the shuttle, we chatted with a guy who was doing the Pacific Crest Trail and gave him a ride down into Mammoth Lakes. He started on the Mexico border on April 24 and still had about 5 months to go. He'd done the Appalachian Trail last year and was planning on tackling the Continental Divide next year - quite an interesting lifestyle.

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area

An unexpected stop on our way to Kanab was the Glen Canyon Dam, and the visitor center there. We stopped to talk to Ranger Don, who was really knowledgeable about the area and gave us great information about not only the Dam, but the entire area. The Dam was built in the 1960s after a long debate about where to build it; the Sierra Club fought against damming the river at Dinosaur National Park and won, and since the Page area at the time was completely unknown, its where they decided to build. They first had to build a bridge, then the dam, and as it was happening, the town of Page grew. It’s actually unfortunate, because they flooded many ancient ruin sites, as well as damming the source of the river that created the Grand Canyon. Nonetheless, it’s necessary to protect the water that goes to seven states as well as Mexico. It also provides a lot of hydroelectric power to the region.

We went on a short hike to the hanging gardens, an area near the dam where an entire wall of an alcove is growing with ferns and other plants because of a large seep. Not sure why that place in particular was so lush, but it was interesting to see, particularly because it is so much hotter here than it has been in the last few places where we've seen alcoves.

Grand Canyon National Park, North Rim

After driving Carrie home, we set off into Arizona. We took a slight detour to drive Old Route 66, stopping to see the Hackberry General Store and getting lunch at Delgadillo’s Sno Cap in Seligman. Definitely had the charm and feel of old-time Rt 66! We made it to GC in the afternoon, and it was CROWDED. At least the weather was nice - around 90 degrees, which to us felt totally manageable. The Visitors Center doesn’t have too much info (but there are several different museums), so we picked up Jr Ranger books at the store and watched the film. When we went back to get our badges, the GC Association worker who checked us out gave us great tips on where to go, and after we explained our project, he told us about a little-known spot known as Shoshone Point. It was a sacred site for several Native American tribes, and still used for ceremonies, weddings, and other rituals.

We stopped first at the Yavapai Geology Museum (taking the shuttle all the way around since we got on the East instead of Westbound bus) and learned about the fascinating makeup of the canyon. We got our first glimpse of the canyon - no matter where you are along the rim, there’s going to be an amazing view, and each spot is different and unique. But each spot is also usually crowded, and for the most part you get a great panorama

that spans about 180 degrees. So it was a complete lucky surprise when we hiked out to Shoshone Point, a small promontory jutting out into the canyon. You can see the canyon at least 270 degrees around you - maybe more. We hiked the 1.25 or so miles in, walking as fast as we could to try to catch the last bits of light - we’d just missed sunset, arriving about 15 minutes too late. But it was still light enough to truly appreciate what a great vantage we had. We stayed until after everyone else left, and had the dinner that we’d brought, before hiking out in the dark. Definitely a lucky and memorable spot.

For a bit of a change of perspective, we went to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. This side of the canyon, because of continuing uplift, is actually 1000 feet higher elevation than the South Rim - which means totally different climate and feel. There are meadows and aspen and pine forests on the way to the rim, and the canyon itself is more gradual (as opposed to the South side, which has a steeper drop-off). We hiked to Bright Angel Point, which had a sweeping overlook, then drove to Cape Royal for another look into the canyon. From there we could see Angel's Window, a hole in the Kaibab limestone layer. There's also a fantastic view into the canyon all the way to the South Rim - you can tell you're looking down a more gradual slope than you would from the South Rim of the canyon.

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument

The Grand Staircase is a huge area, encompassing much of the eroded uplifted plateau that shows the geologic progression through time. The entire staircase stretches from its highest points at Cedar Breaks and Bryce, and going downhill to its lowest point at the Grand Canyon. Because so many geologic layers are visible, numerous dinosaur fossils have been found all around the area.

The Staircase dominates the western part of the monument, the center section is known as the Kaiparowits Plateau, and the eastern side are the Canyons of the Escalante. This eastern section is where we spent the day hiking, doing a round trip hike through Peek-a-boo Gulch and Spooky Gulch.

This was one of the most fun and engaging hikes all of us have ever done. To get into Peek-a-boo, we had to wade through a thigh-high pool of muddy water (complete with its resident frog!) and climb up slippery sandstone rock face to get into the entrance. From there, we scrambled, crawled, and wodged (we made up that word) our way through tight wavy sandstone slits through the canyon.

One of the most iconic hikes here is the Spooky Gulch slot canyon. Spooky Gulch was even tighter - not only did we have to carefully maneuver our way down a ~10 ft drop into the canyon, but the slots were so small that you had to take off backpacks and squeeze and wedge your way through. At some point, the slit was so small that even my feet were too wide to fit into the cracks! It was definitely one of the most fun hikes I've ever done. We processed some early footage of our hike through the slot canyon, which you can view in a VR headset or by scrolling around with your mouse.

Hovenweep National Monument

The final stop of the day was to Hovenweep, where we walked the Square Tower Loop. This cluster of ruins was the largest group of Hovenweep's groups, housing up to 500 people between 1200 - 1300CE. We walked around Little Ruin Canyon, stopping to see the many structures that were perched on the canyon rim, tucked into alcoves, or built on and around boulders.

Hubbel Trading Post National Historic Site

Hubbell Trading Post is an old Navajo trading site that was founded by JL Hubbell in 1878 after the Navajo people returned to the area following the Long Walk. During this stain on US History, the government forced the native people to leave their homelands and walk to exile in Fort Sumner, New Mexico. When they returned four years later, their homes were gone, their crops destroyed, and their livestock slaughtered. Hubbell helped the Navajo by supplying goods during their recovery. The trading post was run by the Hubbell family all the way through until it was sold to the NPS in 1960; it is still considered an active trading post.

Manzanar National Historic Site

After a morning of trying to fix our rental car (several calls to multiple Enterprise numbers, a visit to Firestone, a visit to Enterprise Bishop, more phone calls, and a promise of a call back) - resulting in us having a car with no brake lights for the next 3 days - we finally made it to Manzanar. We started in the visitor's center, where we worked on our Junior Ranger badges, watched the film, and learned about individual stories.

Manzanar is a one-square mile "relocation center" that housed over 11,000 American citizens from March 21, 1942 until November 21, 1945, as a result of Japan's bombing of Pearl Harbor. Anyone with Japanese heritage living in Washington, Oregon, and California was required to relocate. People were divided into 36 Blocks; each block had 14 barracks divided into apartments, latrines, laundry room, ironing room, mess hall, and gardens.

Today, there are three original buildings left standing - after Manzanar closed, most of the structures were sold off by the US government. In Block 14, there are reconstructed barracks, a latrine, and mess hall where you can see the challenging lifestyle people had to endure. The rooms were stifling hot, and a constant wind blows dust and dirt through cracks and windows. In the latrine, communal toilets and showers meant absolutely no privacy; in the mess hall, food was cooked in bulk and not suited to Japanese tastes.

We took the driving tour around the site, stopping first for lunch in some shade, then at Merritt Park to see the remnants of what was once a beautiful oasis with lawns, bridges, a pond, and flower gardens. Our final stop was at the shrine in the cemetery, where people have left hundreds of origami cranes. Some were faded to almost a colorless grey; others were vibrant and rainbow-hued.

Mesa Verde National Park

The cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde are spectacular, and we were lucky enough to have several days to enjoy them. While there are over 1200 ruins found, around 600 are dwellings (the others being storage facilities), and only a small handful can be visited. Most require a ranger-led tour, and we got tickets to all four of them - Long House, Balcony House, Cliff Palace, and Mug House. Cliff dwellings are primarily made up of sandstone, mortar, and wooden beams. The sandstone blocks were shaped by chipping at them with harder granite collected from river beds. Mortar was made with soil, water, and ash, and smaller stones were fitted into the gaps in the mortar to add stability to the walls.

On Friday, we got to the Long House lot early, so we quickly visited the Step House - the only self-guided tour. it's the smallest of the cliff dwellings, and has several reconstructed pit houses along with pueblos. It was interesting because there are two distinct occupations at the site - pithouses remain from a Modified Basketmaker site, dating to AD 626, and the remaining masonry pueblos are built on top of it from AD 1226.

We then visited Long House, the second largest dwelling in the park. Along the way, we saw the checkdams that the ancient Puebloans had built to help capture water and soil. Because they were practicing dry farming (where they relied solely on precipitation to water their crops), they needed to keep as much water in the soil as they could. Mesa Verde isn't a real 'mesa' - an elevated piece of land with a flat top - it's actually a cuesta - meaning it has a slight slope. This slope meant that water would reliably run down a specific direction, and the Puebloans could then build these checkdams in the right places to slow the water and allow it to seep deeper into the soil. Checkdams also allowed them to capture the rich runoff, giving them more fertile soil for their crops.

We also saw steep cliffs that had hand- and toe-holds carved into the rockface. You can only imagine how difficult it would be to navigate these cliffs while carrying baskets of water or heavy rocks. Why did the ancestral Puebloans decide to move off the tops of the mesa and down into the cliff alcoves? The Mesa Verde area is a desert, and water is very scarce. Most likely the people were following the water. When the area was formed, it was under multiple iterations of inland seas. Layers of silt - sandstone - and organic matter - shale - built up over time. The sandstone soaks up rainwater, stopping only when it reaches a shale layer. Years of continual freezing and defrosting weakens the sandstone until it finally erodes away against the shale layer, forming the alcoves. Also at these alcoves are seep springs, where water leeches out of the sandstone layer and can be collected in carved basins on the shale layer. This is the main source of water for the cliff dwellers.

Immediately after our Long House tour, we drove to the Archaeological Museum to meet with Ranger Jill. She had prepared quite a bit of material for us, and spent almost 2 hours talking to us about her thoughts and experiences at Mesa Verde.

Our final hike of the day was to Petroglyph Point - a really fun trail down the canyon to view petroglyphs, then back up to the rim to complete the loop. It was a great way to end the day.

The next morning, we left early (6:15AM) in order to get into the park for our Balcony House tour. Balcony House, a medium-sized dwelling, was constructed and occupied in the 13th century and named for the two small balconies that can be seen extending from two of existing rock walls. This was by far the most fun tour, with several tunnels, tight passageways, and ladders.

How were the building in Mesa Verde made? The three main materials for all cliff dwellings were sandstone, mortar, and wooden beams. The sandstone was shaped into blocks using harder stones that had been gathered from riverbeds (far away) and brought to the sites. The mortar was a mixture of clay, water, and ash. By adding smaller stones into gaps in the mortar (called 'chinking'), walls could be made more stable. Over the walls were usually earthen plaster that could then be painted (but many of the plaster walls have since eroded away). Immediately after the Balcony House tour, we had a Cliff Palace tour. This is the largest of the cliff dwellings in Mesa Verde (and in North America), with 150 room and 23 kivas for a population of around 100 people. (In contrast, most dwellings in the Park have between 1-5 rooms each, and many are single room storage units.)

We then visited the Mesa Top Drive sites to see examples of pithouses and early pueblo villages (from AD 600-900). From the drive we also had an excellent overlook at Sun Point View, which shows a dozen cliff dwellings in alcoves in two different canyons, including Cliff Palace.

The final stop of the day was to Sun Temple, a strange structure built with thick double walls and seemed to be unfinished. It was built in AD1250, and it is thought that it was perhaps built specifically for worship, and as a sacrifice to the gods since they were running out of natural resources and were in the midst of a prolonged drought.

On our final day, we took the Mug House tour - a backcountry hike to one of the lesser-visited cliff dwellings. It was a small group of only 10 visitors, and the trail was more scrambling over boulders and dodging rare endemic plants. Along the way, we passed by two other alcoves - one of which had a good example of a pictogram, a long zigzag that was compared to the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl. To me, it looked more like a mountain range... but I guess that's why I'm not an archaeologist…

Mug House itself was named for the multiple mugs found there, and it's known for having some different architecture than some of the other cliff dwellings. Notably, there is an excellent example of a classic Mesa Verde Keyhole kiva, but there is also a kiva with 4 alcoves, and another with 8 alcoves. It's also one of the few alcoves that doesn't have an active seep spring - instead, nearby is a cistern that holds around 500 gallons.

Natural Bridges National Monument

Meandering streams cutting into canyons are what form the bridges at Natural Bridges NM. There are three main bridges that can be viewed in the small park, which you can view from overlooks. These bridges are formed when a slow river makes horseshoes as it meanders in its path. At some point, the river decides to cut a detour, eroding through the thin neck of rock that separates the flow. The stream undercuts the barrier, and seeping moisture weakens the top and helps it to erode - until finally it breaks through and a bridge is formed. We hiked to the bottom of the canyon to see Owachomo Bridge from a different viewpoint. It was a bit unbelievable to know these bridges are all still eroding, and eventually they'll crumble and collapse, even as new bridges are forming.

On our way to the next stop, we drove through some pretty spectacular Southwestern landscapes. We drove the Moki Dugway to the Valley of the Gods, then stopped for the night in Monument Valley. We stayed in a traditional Navajo hogan, a circular dirt/timber/clay structure that had been built in 1934 by our host's great grandmother. Really cozy, and quite comfortable.

Navajo National Monument

This small park is interesting since the two main viewpoints, Betatakin and Keet Seel, are both Ancient Puebloan ruins and not Navajo. The park is named because the Navajo moved in later on, and still occupy the land. But back in the 1200s, the ancestors of the Hopi people came and built in alcoves of Tsegi Canyon. Because the Navajo believed it was bad luck to enter these sites, they stayed basically untouched, and to this day they are some of the best preserved ruins in the area. We got lucky and made it in time for the guided ranger hike down to the canyon bottom, where we could see Betatakin up close. Normally you can't go down into the canyon, so it was nice having a semi-private tour (there was only one other person). The bottom of the canyon has a lot of water, and has a relic forest still there with aspen trees, gambel oak, and horsetail. Looking down, it is really really green considering we're still in the middle of the Arizona desert.

One of the coolest things at Betatakin was the pictographs seen on hill to the side of the site. There are four clan symbols - Deer, Fire, Flute, and Water. The Fire symbol was interesting because it looks like a man doing a fire dance, and it has a supernatural feel to it. The Flute symbol was the strangest - not sure why it represents a flute, since it looked more like a pie chart or a Pacman. Even so, it was cool seeing them all lined up.

Petrified Forest National Park

We spent an entire day at Petrified Forest, a park that may be named for the petrified trees but is really remarkable because of its landscape. Half the park is known as the Painted Desert, and colorful mesas and teepees abound.

Ranger Rick, the Chief of Interpretation, has been helping me with navigating the NPS system and with connecting me to people, and he introduced me to Ian, an artist-in-residence at Petrified Forest who was working on a VR project. We just missed him by a few days, but he sent a great list of places to go for good 360 shots.

We stopped first at the Rainbow Forest Visitors Center, where we walked around the Giant Logs Trail to see up close a number of petrified logs. 225 million years ago, before the continent of Pangaea broke apart, the area of Petrified Forest was about 4° north of the Equator. It was a wet, tropical rainforest, covered in forests, lakes, and rivers. For millions of years, silt from those waters accumulated, setting the foundation for the

layers found today.

When logs from downed trees were covered by silt from periodic flooding, the process of petrification began. silica-rich water seeped into the wood, slowly replacing the organic matter with quartz. Mineral impurities in the quartz give the petrified logs their different colors.

The various flood deposits also created the colorful layers in the rocks, which are now exposed due to water and wind erosion. We also saw several bright logs at the Crystal Forest trail.

The landscape at Blue Mesa and the Blue Trees Trail is absolutely otherworldly - with rich colors in the blue/purple/grey spectrum. Every time we'd walk past someone on the trail, we'd catch their eye and we'd all just shake our heads and murmur, "can you believe this?" in a reverent, disbelieving tone.

Our next stop was Newspaper Rock, to see the petroglyphs. We could only see them from above, but there were some very clear figures that could be seen from the overlook.

Petrified Forest is also interesting because of the beautiful landscape known as the Painted Desert. Old Route 66 ran straight through the park, and the Painted Desert Inn was built as a stopping point on the road for people to get food or spend the night. The inn is now a historic

site, with a great overlook into the Painted Desert.

Our final stop was Puerco Pueblo, a prehistoric settlement on the Rio Puerco built by ancestral Puebloan people. More interestingly, there are lots of petroglyphs in the area, including one of the sun, which is illuminated by a ray of light from a crack between two rocks that aligns perfectly during the summer solstice.

Did you know? There are two kinds of rock art: Petroglyphs are designs carved into rock; pictographs are painted on.

Pipe Spring National Monument

When we drove back down towards Kanab, the temperature quickly rose from 62 on the rim to the upper 80s. By the time we got to Pipe Springs, it was hot and really windy, with lots of lightning. At the end of our picnic lunch, fat raindrops had begun to fall right as we were walking over for the Fort tour. We met a ranger on the way back who was carrying fresh eggs; she gave us 4 of them and we decided to bring them back to the car so that we wouldn't have to walk around with them. Just as we were heading back, the skies opened up and a monsoon downpour began - the 2 minute run to the Fort (also known as Winsor Castle) got us completely drenched.

This was an interesting monument, mainly because the history that is preserved isn't necessarily the most kind to the Native Americans. In the 1860s, the Mormons were paying tithes to the church in the form of cattle. This meant the Church owned hundreds - maybe thousands of head of cattle, with nowhere to put them. Brigham Young looked around for a place, and decided Pipe Spring was the perfect place to build a fort. The problem was, he built it directly over the 'spring' of Pipe Spring - the only water source for the local native Kaibab Paiutes that already lived in the area. They essentially took away the only source of water, and on top of that, their cattle destroyed the native grasses that the Paiutes depended on for survival. In essence, the settlement decimated the Paiute population - driving the number from around 1200 to a total of 76 in the span of less than 50 years.

On their own survival story, the Mormons were trying to preserve their way of life and establish their own sovereign 'kingdom,' away from the rules of the US Government. The main bone of contention at this point was the practice of polygamy, and Winsor Castle was a hiding place for many plural wives of mormon settlers from further north. It also became a stopping point for people passing through on to the big Mormon temple at St. George, where many couples went to get married.

Rainbow Bridge National Monument

An iconic photo spot in Glen Canyon is Horseshoe Bend, a huge meander of the Colorado River just downriver from the Glen Canyon Dam. The drop down to the bottom is 1,000 feet down, and it’s a sweeping overlook that is truly impressive. These meanders are really interesting - eventually, the rock at the start of the turn will wear away and the river will break through, creating a natural bridge at the narrow part of the peninsula of rock - like at Rainbow Bridge.

One of the more remote parks in the nation is Rainbow Bridge National Monument - the largest natural bridge in the world, located on Lake Powell in the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. It's not easy to get to - located in a remote canyon, the only ways to get there are by boat, helicopter, or a several-day hiking trip. We took the 3.5 hour ferry ride from Wahweap Marina, through about 50 miles of Lake Powell.

It's a beautiful trip down the river, and really interesting to see how much the water level fluctuates. Around Wahweap, the lake is around 350 feet deep; closer to the Glen Canyon Dam, it reaches a depth of around 500 feet. It was a really hot 1-mile hike up to the bridge, and although you can't walk under the bridge (in deference to the Navajo, who believe the site to be sacred), you can hike around it for different views. It’s bigger than you'd think - the Statue of Liberty could stand under it! Rainbow Bridge is a sacred Navajo site and named so because of an old legend - where two brothers climbed up the rainbow to ask their father the Sun for help in saving the world. The rainbow was turned to stone as a memorial to their success.

We also stopped at the Wahweap Overlook, for an overview of Lake Powell and the Glen Canyon Dam. Gorgeous turquoise waters, and very impressive to think of the vast scope of the lake and what the dam created.

Sunset Crater National Monument, Wupatki National Monument

North of Walnut Canyon is Sunset Crater. We stopped at the Visitors Center and talked to Ranger Case, who gave us some great information about the area and the people that lived here. Sunset Crater erupted about 1000 years ago, chasing away the people who lived here. But when it erupted, winds blew the ash to the northeast, depositing a rich layer on the

ground that caused the soil to become fertile and trapped water underneath (which lasted for about 100 years). Because of this, Wupatki was settled between 1100 and 1225-ish. Essentially, Wupatki and Sunset Crater are intricately tied together; Wupatki wouldn’t exist without Sunset’s eruption.

Also, did you know: A bubble of magma that slowly rises and hardens without breaking the surface of the earth is called a pluton - it’s usually a much harder material than the earth around it, so the surrounding soil erodes away leaving these plutonic hills and mountains. On the other hand, if the magma bubble breaks the surface, magma turns to lava, and the resulting mound is a volcano. Plutons are named after PLUTO, Roman god of the underworld; Volcanoes are named after VULCAN, Roman god of fire.

Tuzigoot National Monument

It was a ridiculous day today - getting Jr ranger badges and going on short hikes at FIVE different sites! Granted, they are all small and in the Flagstaff area, but I’m still exhausted.

The day started early by driving down to Tuzigoot, an ancient Sinagua pueblo ruin in the Verde Valley. The pueblo has 110 rooms, some 2- and 3-stories, all built of stone on a natural outcrop with a great view of the valley. It was most likely built between 1100 and 1400CE. It’s reconstructed, and it is amazing how they did so after seeing the pictures

of the condition they found it in.

Near Tuzigoot is another pueblo, Montezuma Castle. This ruin is very different in feel - it’s 90 ft high on a cliff wall, built into an alcove, and most likely housed several different families much like a high-rise apartment. Its location not only keeps it cool during hot summer

months as well as protecting it from annual flooding. Access was from a series

of ladders, that could be removed to keep it safe from intruders.

Walnut Canyon National Monument

After driving back up through Flagstaff, we stopped at Walnut Canyon. This site also has cliff dwellings, but these are more horizontal than vertical, and span both sides of the canyon. The most interesting section is the Island, built on a limestone cliff on an oxbow

of Walnut Creek. The back walls and roofs of the dwellings are part of the cliff, and the view from the front is absolutely breathtaking. We walked down the 240 steps and around the Island, then back up to the Visitors Center.

Yosemite National Park

We picked up Carrie, who is joining us for the first five nights, on our way out to Yosemite. Carrie is a middle school science teacher from Oakland, who I met a few years ago at a teacher conference. In exchange for crashing the trip, Carrie is going to help us with writing curriculum and coming up with lesson ideas.

We drove straight through to Wawona, making it exactly on time for our 1:30 meeting with Ranger Alejandra. Alejandra gave us some great tips for places to go (some that we hadn't thought of, like the top of Sentinel Dome) as well as telling us about moon bows.